AN INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVE OF RECONCILIATION AND ART

By Tatiana Zamorano-Henriquez

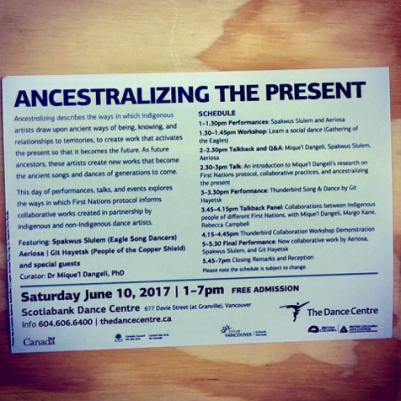

Photo Courtesy of Dr. Mique’l Dangeli

*Permission to reprint granted by the Vancouver Arts Colloquium Society

Art plays an integral role in the process of reconciliation as it is a way in which people, nations, and cultures can “say what goes unsaid” (Dr. Dangeli). For this reason, art “has a really important place within the reconciliation dialogue and… more funding should go to supporting Indigenous people creating their art (culture and way of being) with and for their people rather than reconciliation being focused on Indigenous and non-Indigenous collaborations because we have so much to reconcile within our own communities” (Dr. Dangeli) first and foremost.

The process of reconciliation itself is a challenging one, and the difficulty of this process comes in understanding what reconciliation truly embodies. I had the privilege to sit down with Dr. Mique’l Dangeli, an Indigenous visual and performing artist who holds a PhD in Northwest Coast First Nations art history , while also working as a curator and a professor. As I sat in her and her husband’s art studio, I was so encompassed by culture, histories, and knowledge that it was as if the entire room was alive. It was breathtaking and moving all at the same time. It was here, as she painted one of her collaboration pieces that she had done with her husband, Mike Dangeli, that she relayed to me her powerful words and guidance for a legitimate form of reconciliation and the role of art in this process. Through her words, what profoundly resonated with me was the following statement: “Education is important, but if the focus is always outwards and not inwards, then we are not strengthening our practices we are just practicing for others” (Dr. Dangeli).

These words were striking, as they deeply echoed the embodiment of a true, pure, and honest form of reconciliation that I understand as a process in which Indigenous people are and need to be the protagonists of. This is a process in which Indigenous people need to reconcile themselves first, in order to achieve reconciliation and resurgence. However, if there is something that I have learned as a student who majored in Sociology and minored in First Nation and Indigenous studies, it is that processes such as these are works in progress, and that there is always room for growth. Therefore, I believe that one essential factor that we must consider in order for progress in these areas to occur is an approach that was passed on to me by my Indigenous mentors and professors: We must approach these methods with an open mind and an open heart and do this work in a good way. It is this very approach that will enable all individuals to open their hearts and minds to new perspectives, ways of knowing, and ideas that are fundamental in igniting these conversations, conducting these processes and collaborations in fair, innovative, and genuine forms.

Having our minds and hearts open to this discussion and keeping to Dr. Dangeli’s statement, I wanted to put Dr. Dangeli’s voice at the forefront of this article to make her the protagonist of this discussion.

TZH: Could you tell me a bit about yourself your background and the artistic work that you do within and outside your community?

Dr. Dangeli: I am Tsimshian First Nations, from Metakatla, Alaska, which is the only Indian reserve in Alaska. It is the last island on the panhandle, very close to Prince Rupert, BC, and just outside of Ketchikan, Alaska. I was born and raised in our community, where what I now think about and talk about as art was and is our culture. I grew up around … dance, [it] was our practice of dancing [that] was my first art form. Then our visual art was offered in our school district, so I started taking classes in what is referred to as Northwest coast art as most people know it. Tsimshian art in particular, when I was in grade eight and all the way through to grade twelve. I [also] went out to apprentice with a couple [of] master carvers. My husband and I, Mike Dangeli, also grew up dancing and apprenticing with artists in his family including his grandmother and his uncle, who are both master artists themselves. Now we have been leading the Git Hayetsk dancers in Vancouver for the past fourteen years. He and I collaborate a lot on different projects because I am a choreographer and he is a composer, so we create a lot of new songs and dances that are used within our dance group and within ceremonies in our communities. Also, we still continue to collaborate with our visual art practices because that is how we met; we were both apprenticing with the same master carver, and we kind of fell in love through the process of our apprenticeships. I just finished a two-year artist residency at the Scotiabank Dance Centre as a dance artist in residence, in June of this year with an event called Ancestralizing the Present.

Then, in 2015 I graduated from UBC with my PhD in Northwest Coast Art History. So my relationship to art with Indigenous art, First Nations art [and] in particular art of the Northwest Coast is multifaceted in that I am a visual artist, a performing artist, I have my PhD in this area, I am a curator and a professor. [Also,] I just recently became a professor of Alaska Native Studies at the university of Alaska Southeast in Juneau but I decided that I wanted to focus on language revitalization. My language revitalization, so I… left that tenure track position to help my nation build immersion programs and language nests so I [could] teach Sm’algyax, which is my people’s language.

TZH: Why is the work you do important and what do you hope to achieve?

Dr. Dangeli: What I hope to achieve — through our dance group in particular — [is that] it is really about our community, it is [about] the perpetuation of our cultural practices, our songs, our dance our visual art. We are a mask dancing group, from the regalia, to the masks that we dance, it is about the perpetuation of those practices and really giving our people here in the city an opportunity to express who they are and the way of our ancestors. I feel that having moved to Vancouver, I did not realize how unique my upbringing was, to have been raised in my community, with my family and immersed in my cultural practices. When we started this dance group I came to a very quick realization that the majority of the people who were joining had never danced before, [they] had never had the opportunity to dance before because they grew up… away from their home communities. That is the priority for my husband and I: Educating the public is a part of what we do, but it is secondary to what we do for our own people. Educating is important but if the focus is always outwards, and not inwards, than we are not strengthening our practices, we are just practicing for others. So we are really focused in taking care of our community here. Our dance group performs at events all over the city; we just did the Surrey Fusion Festival, and [various] other events. We utilize the funds that we raise through dancing to help our dancers make regalia [and] to pay for us to go and attend ceremonies back in our home communities. We just recently came back from Teslin, Yukon, dancing at the Haa Ḵusteeyí festival [where] we were a featured dance group there. [Also], just this summer we danced in Calgary at the Children’s Festival, Ottawa at the National Art Centre, in Toronto, and Idyllwild California at the Idyllwild Art School where my husband was teaching.

TZH: Why is art pivotal in Indigenous communities?

Dr. Dangeli: I think I can answer in a general way that speaks to both my community, as well as our larger community. I would say that art is interwoven in every aspect of who we are as Indigenous people: through our relationship to the land, the waterways, through our ancient oral histories [and] through our relationships to one another. A really overused kind of saying that there is, is that there is no word for art in our language as Indigenous people. I say that there’s actually hundreds of words, there are thousands of words, because there are words for all of the materials that we use in our art. There are words for the methods and techniques that we use to create, there are words for what it is we have created. For example, our masks amongst our people are referred to as Nax Nox; it is a highest form of supernatural powers amongst our people. I feel that there really is no differentiating in our ways of knowing and being. The difference between art and life: it is really integral to our way of life, and it is really anthropology and ethnology that have defined things in terms of utilitarian-meaning everyday objects and ceremonial. I really believe and I have seen, experienced, and witnessed in many different Indigenous cultures that there are no clear cut divisions in that way. That what is utilitarian to anthropologists also has ceremonial functions and vice versa, so I would say that art is really life for Indigenous people.

TZH: I know that your journey has led you to work both with Indigenous and non-Indigenous people how have you been able to use art as a tool to bring people of diverse cultures together or how have you seen art bring people of diverse cultures together?

Dr. Dangeli: We definitely use art as a bridge between non-Indigenous people and us through both our performing art practices and our visual art practices. Ancestralizing the Present — the dance event that I curated to conclude my artist residency at the Scotiabank Dance Center — was focus[ed] on Indigenous and non-Indigenous collaborations. I brought in a case study from my dissertation, which was a collaboration between S7aplek (Bob Baker) and Julia Taffe of Aeriosa. They performed their collaboration as a part of the dance event, [and] I presented my research on their process of collaboration. Then we had a Q and A, and my dance group and I collaborated with them on a new piece that premiered at that event. The whole emphasis of that event was to show that non-Indigenous and Indigenous people have been collaborating together in very productive, really generative ways before reconciliation was a thing, before it was popular and a sign of being politically aware or savvy. The way that reconciliation has been taken up by many non-Indigenous visual artists and performing artists is in terms of money. Taking up these opportunities for reconciliation grants to write up a grant and then late in the process bring aboard Indigenous artists. What I was showing in [the] Aeriosa and Spakwus Slulum collaboration that was in 2011 was an Indigenous-led collaboration; and that really is what reconciliation is about to me. It is about non-Indigenous people taking the backseat and not being the ones that are driving these collaborations in the name of reconciliation, but [instead] taking the time to learn from Indigenous peoples and the ways in which they create. On the Northwest Coast, our primary method of creation is through our protocols, which are our bodies of Indigenous laws that are essential to new songs and dances and the performance of our ancient songs and dances. Until non-Indigenous artists stop working within the colonial mindset that has been ingrained [into] their mentalit[ies] and their practices, [and until they] realize that coming to Indigenous artists and saying, “I want to collaborate with you, this is what I have in mind” or “This is what I am going to do”, rather than saying, “I would love to collaborate with you, what is it that you could see?” [or] “You know, here is my practice: what is it that you could see for possibilities in terms of collaboration?”, [rather] than by telling us how to collaborate by telling us the projects that we should collaborate on. [This] is a continuation of colonial paternalism, as though we are not critical thinkers, or cannot do this work on our own; that they need to lead us by the hand in some respects, when really, that is just a continuation of colonialism, rather than reconciliation.

It is clearly non-Indigenous work with sprinkles of Indigeneity through inclusion. Ancestralizing the Present was about show[ing] how meaningful and deep the practice is when it is an indigenously led collaboration.

TZH: What is your perspective of Reconciliation?

Dr. Dangeli: I think having grown up in the U.S, and [having done] all of my graduate school at the University of British Columbia [while] continuing to go home for ceremonies and travelling a lot through the U.S for different events, I am definitely very critical about the way reconciliation is used. In Canada, there are ways of rendering it meaningless: through some of what I had previously mentioned, as well as when the Truth and Reconciliation Committee was happening: I was seeing [reconciliation] as another form of missionisation [that] non- Indigenous people were taking up in a way that they were getting upset with Indigenous people when they were not on board. We should be able to self-determine as human beings whether or not we have forgiveness for what has happened and whether or not we are ready to reconcile. Having also the perspective of being in the U.S — and I do not want to say from the U.S because my people are border people, between what is now Alaska and Northern BC — we have always been in that area so it is hard for us to define our citizenship and those simple measures but I see [reconciliation] as something that is very hopeful. When I look at the U.S, especially right now with such intense racial tensions and this public resurgence of white supremacy in the U.S, I am thankful that Canada is where it is the dialogue and at least their self reflective nature to say, [and] agree that they have done something terribly wrong and that those wrongs can never be made right. That they are working on including these histories in the narrative of Canada, instead of the narrative of Canadian history that excluded us for so long and excluded the atrocities that led to the founding of this country which is only 150 years old: it is so… recent. When you think of Indigenous histories, the numbers are anywhere from fifteen thousands, eighteen thousand, thirty thousand, hundreds of thousands of years that we have been in this place. I think if [reconciliation] is done with a critical mindset, [in which] it is not just [an] easy [process where you] bring Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in a room to work together and [then call it] reconciliation [because] it really [is] not. There is a lot more to it, it has to be Indigenously led, an Indigenously self-determined process that supports Indigenous sovereignty that acknowledges Indigenous land rights. Starting at the residential school history… is just one of thousands of starting places, [this]… is the starting place that launched this conversation about reconciliation off, but there is no reconciliation without recognizing the land rights of Indigenous peoples and not just in a way [where]… the city recognizes that they are on the unceded territory of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh people, [but to push this issue further] what the city should do is then support the work that those nations are doing to get the federal government to recognize their land rights, it has to be more than words.”

TZH: Do you believe that there is a place for art in the process of reconciliation?

Dr. Dangeli: Yes, I think that art gets away with a lot more than people who have governmental authority. If they were to express some of the opinions that were expressed through arts, they may lose their jobs. I think one of the many roles of artists is to say what goes unsaid, and some of it is so obviously unsaid or understated in the way that those in particular political positions have to express themselves in order to come across [as neutral], [but] there is nothing that is really neutral about anything that we do as human beings. This [neutrality] makes it more palatable — easier to digest — and artists, I feel, do not have to worry about that. Some artwork may be less palatable than others, but the viewers have a choice about what it is they want to give their time and energy to. I love that about the art. It has a really important place within the reconciliation dialogue, and I think that more of the funding should go to Indigenous people creating their art with and for their people rather than reconciliation being focused on Indigenous and non-Indigenous collaborations. We have so much to reconcile within our own communities; for example, I have resigned from a tenure track position at the university to work with a kindergarten-through-grade-twelve Montessori-style program at a school called Na Aksa Gyilak’yoo in Kitsumkalum, BC. I feel [that] because of the extreme endangered state of my language, this opportunity to work with fluent speakers may only be around maybe for the next ten years, but could possibly be gone in the next five to eight years. If Canada would put more money into really recuperating or healing the damage that was done to our language and cultural practices within our community, that to me is more reconciliation than non-Indigenous and Indigenous people working on these art projects. [Instead,] this money needs to go back to undoing the damage that residential schools did.

If Canada would put more of their money into really recuperating or healing the damage that was done to our language and cultural practices within our community, that to me is more reconciliation than non-Indigenous and Indigenous people working on these art projects.

TZH: Do you feel that art can be used as a form of resurgence for Indigenous nations?

Dr. Dangeli: Art is definitely a form of resurgence for Indigenous peoples in many different ways. The ways that it brings communities together through ceremonial and non-ceremonial events, the intergenerational teachings that happen through the production of art, the way that language work can be brought in, ways that are instrumental to the creation of art. So yes, it is the medium in which our ways of being survived, even if it was in kind of a muted form that was made for tourists. When missionaries, Indian agents and others saw it as our entry into the cash economy, then it became kind of a more subtle form, or even just an entirely different form [of art] so that it would be of interest to buyers; but even within those forms [they] may not look like they carry any knowledge. They may look like a caricature of what was being produced prior, [but] even then it still carries knowledge.

TZH: I am currently part of an initiative called Beyond Music that was founded in collaboration with the Musqueam community. This is an after-school program in which Indigenous youth are offered free violin and songwriting lessons. The initiative is a cross pollination of diverse cultures coming together through art: Do you believe initiatives such as these have a place in the process of reconciliation?

Dr. Dangeli: I do believe initiatives like that can have a place in reconciliation, as long as it is not another form of assimilation [and] it is not another form of essentially trying to formulate the identity of our youth around concepts of Western music and Western culture. One of the reasons why Indian bands emerged — everything from bass bands to rock bands — was because within residential schools, the emphasis was to remove the songs and dances of our people from our memory and abilities [so they could] introduce us to instruments, especially those instruments that were associated with the church. I think that there can be [a place for these initiatives]. An artist that I can think of that has done an amazing job of Indigenizing a very Western genre is Chris Dirksen and her cello music. Being an Anishinaabe artist and working and collaborating with different artists, both Indigenous and non-, from all sorts of genres. So I think it can have a place, there just has to be a careful balance to say that young people are all of our people, are Indigenous no matter what we do, no matter what clothes we wear, no matter what instruments we are playing. Whether an artist is carving a totem pole, or they are creating a film those are Indigenous art practices because the person creating them and doing the work is Indigenous. At the same time, my hope is that more programs can offer teachings and practices that were ancient practices amongst our people because our art forms are constantly changing. That is why they have incredible vitality and strength. I mean, as I am talking to you, I am painting a spray painted canvas of hot pink and green and yellow, and I’m painting an overcoat design on it with this awesome fluorescent green paint; and I do not see it as anything different from the regalia that I just painted for my husband that was more what people would consider traditional or custom, customary colours, as long as they have exposure to it all.

TZH: Keeping reconciliation in mind what would your advice be to those trying to bridge the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people and culture using artistic methods and initiatives?

Dr. Dangeli: My advice is always for our own people, I know that it is really easy as an Indigenous artist to fall into the trap of I have advice for non-Indigenous people. I think were asked to do that more often than not rather, than advice for our own people. I would say for our own people, for Indigenous artists out there that are being pulled into these reconciliation projects or there creating reconciliation projects themselves, is to stay firm, stay true, firm to your beliefs, stay true to your intentions and in Sm’algyax my language we say “ Smgyit Haaytgn” which means stand strong. In this time of reconciliation what you have to say and do as an Indigenous artist is the most important part of the process of reconciliation but more often than not when you are in collaborative work created by non-Indigenous people we will have to fight for space that is rightfully ours–to represent ourselves as we determine and not as how they wish to see us.. Indigenous people are working through their own process of decolonization, some non-Indigenous people are, but I would say the vast majority of non-Indigenous people are not and they fall right back into the colonial construct of non-Indigenous people having positions of power and authority over Indigenous people. So stay true to your intentions, really be firm for what it is that you have in mind for the pieces that you create and “Smgyit Haaytgn”; stand strong in that.

I believe that Dr. Dangeli’s vision for a legitimate form of reconciliation, intertwined with arts and culture in which Indigenous people have to have a protagonist role, is an exemplary model of what everyone should envision for reconciliation. Dr. Dangeli’s profound insight and guidance on this topic should be embraced as a learning lesson for all organizations and individuals that value the concept of reconciliation through the arts. Additionally, what we can all take from this is that reconciliation consists of more than words, it necessitates actions and processes created and determined by Indigenous people and where non-Indigenous organizations and individuals must understand and be willing to embrace a supporting role in a process of reconciliation that is engrained in sovereignty and self determination. When we collectively achieve these objectives, only then will true and honest reconciliation flourish not only through the arts but also through various other avenues, paving the way to an authentic reconciled future.

Dear Keiko Honda, Thank you for making Dr. Dangeli’s vision and voice known to me and others. David Roomy, author and Jungian psychotherapist.